|

||

|

Unravelling Ariadne's thread

|

||

|

In the second of a two-part travel series Mark Sargen reaches Iraklio, the last stop of his literary pilgrimage to Crete Read Sargen's first article "To Nikos Kazantzakis' Grave." On to Iraklio. Our maps are incomplete. We keep encountering streets that don't appear on the page. I attempt to find our way by whim and soon we are lost in a labyrinth of extremely narrow streets. "Didn't we pass that cafe with all the old guys ten minutes ago?" Who knows, they all do look the same, and because the buildings are several storeys high, it is impossible to reckon by landmark. Children stare as we pass. |

The Venetian Loggia, once a meeting place for Iraklio's nobility, now houses the town hall |

|

| They know we're lost. The minutes and blocks whir by while ever deeper into the bowels of Iraklio we drive. Ariadne, where's the bloody thread, child? We finally emerge by Freedom Park, make contact with Mirella's nephew, a student at the local university and meet him at El Greco Park. He graciously takes us into his student digs. We fill him in on our travels to date.He says, "My great great grandfather died at Arkadi. His name was Yiannis Sopasis, though sometimes it appears Sopasis Kouvos." "Is his skull there?" He nods and moments later adds to my inquiries concerning the General Kriepe snatch, "My grandfather, Yiorgos Sopasis was part of the group, though you'll see his name as Hodziyiorgos." |

||

|

What a little island! I look closely at George Sopasis, from a long line of Cretan warriors, a heritage Kazantzakis would admire, now studying computers and applied chemistry, and I can't see it. Can it be true that just beneath the surface of this mild-mannered bourgeois young man lies the sinew and heart of merciless Cretan freedom fighter? Probably. May he never need to know. Later that evening, Mirella and I are wandering the town when |

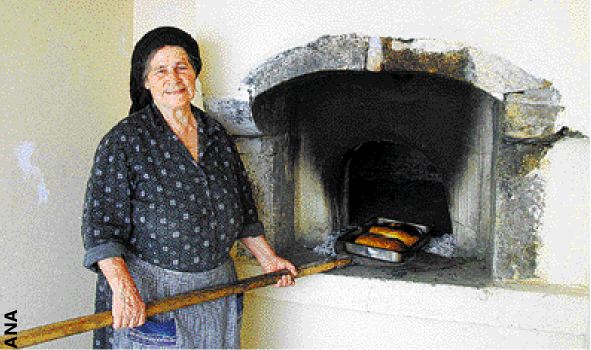

Baking the traditional way in Kolena village |

|

| we hear music and follow the sound to the Platia Ekaterini. There on a stage before the Ayios Minas Cathedral a five-piece Cretan band is holding forth, and they are hot. Two ouds, a guitar, percussionist and lyre accompany much passionate singing. Marvelous. We grab a cafe table 'neath the stars, order beer and luxuriate. The lyre enters the flesh, but not deeply. The long bowed melodies work the surface, prick and titillate, and then saturate the head. We end the evening in a small taverna just off the port with shrimp and fried cheese, mussels and soupes krasakia savoured with much raki. |

||

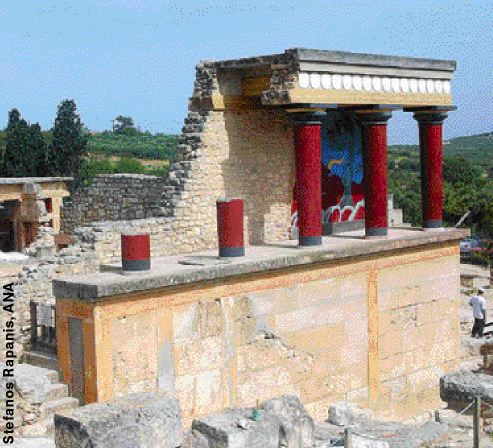

| Iraklio gets very bad press in the guide books: "a huge, noisy, charmless, dusty, concrete conglomeration". But staying and walking within the walls of the old town, the megalo kastro, as Kazantzakis put it, we find much to like: excellent food, lovely bars and cafes, ample parks, an energy with some snap to it. I don't believe it. Arthur Evans claims that this dinky little chair was the throne for the king of all this, the great palace of Knossos? No way. It looks like one of the chairs along the wall in a village church. Something the retired cantor, drooling and half-blind, has flopped himself on. A palace as lavish as this does not connote a humble |

View of Iraklio's beautiful port against the backdrop of the city's concrete buildings |

|

| monarch; on the other hand, he had something going, because the first thing you notice is the absence of fortification. The archaeologists claim that "continuous peace", Pax Minoica, prevailed throughout the island. For hundreds of years. How is this possible? That the peasants wouldn't rise up is easy to understand, more than likely they felt they deserved their lot and that the aristocracy deserved theirs. But what kept the various kings and the no doubt multiples of ambitious princes from raising armies and thrashing it out for power? The pottery, the frescos, are beautiful, but have nothing to say on this point. The little snake goddesses do not speak, frozen forever, breasts bursting from their jackets, adders writhing in their hands, leopards perched upon their heads. On one of the goddess figurines her crown is definitely festooned with opium poppies. She represents, perhaps, the sleep before the big sleep. |

||

| From Knossos we drive serpentine roads southeast towards the hilltop village of Mirtia. The vineyards are heavy with rich succulent fruit flashing golden in the late afternoon light or in forbidding purple bending the vine to breaking. We resist the Dionysian temptation to pull over, strip to the flesh and hurl ourselves into the vineyards. It is a call Kazantzakis would have heard, and resisted, revelling in his strength to withstand the intoxicating call to his blood, the raging heritage he sang and scrambled above. Nothing to distinguish Mirtia, same old mix of poorly built |

The northern entrance to the world-famous Knossos archaeological site |

|

| stone houses amongst badly constructed and far uglier concrete ones. In a small platia a modern sculpture strains to leave the scene but is bolted down, an unwilling sentinel to the Nikos Kazantzakis Museum. A smiling woman sells us tickets, inside it is dark and cool. It's a hodgepodge display: manuscripts, some photos, report cards, a huge collection of foreign editions - he wrote prodigiously, both from inspiration and the need to earn a living. If you know something about his life, it is not very illuminating. Yet there's a grounded, suitably austere feel about the place that brings him and his labours to mind. We are shown a video at the end of our visit, a documentary so ecstatically gushing that a phrase the kids had introduced to me earlier in the day came to mind: "Seegah toh Wow." Chill with the hyperbole, dude. |

||

| Retiring to a cafe on the platia we receive, from two old men seated near, the village stare, a look of complete hypnotic concentration. It is not welcoming. Haven't seen it years, thought this gesture was going the way of the donkey and here, of all places, where thousands of foreigners pass through every year. But really, it is their thirst, or the memory of it, that rays out of their eyes. It is the women, Mirella and Klara, with their flashes of skin, that they are drinking in to the last drop. Yamas. |

Some 4,000 examples of marine life populate Iraklio's Sea World Aquarium |

|

| Back down through the groaning vineyards we roll. Ahead of us, crowded in the back of an open truck, a gang of guest workers are done for the day. Laughing smiles flash in their dark subcontinental faces, so far from Pakistan, Bangladesh. Kazantzakis travelled relentlessly, worked furiously, but I have never seen a photo of him laughing. |

||

Gold signet ring of King Minos with representations of Minoan life |

A 16th century BC alabaster pitcher from Knossos, shaped after the head of a lioness, is on display at Iraklio's Archaeological Museum |

|

"For as long as I remained young, what I desired most deeply was not the cure but the wound... I wanted whatever was most difficult, in other words most worthy of man." Kazantzakis wanted to be an old-fashioned saint, wracked with pain and anguish, maybe tortured for his faith. Damn. I'm of the persuasion that life will hurt you plenty, you will get your share of suffering on this planet, you don't have to seek it out. Anyway, it's not a matter of how much, but what you do with suffering that counts. "I have been ashamed many times in my life because I caught my soul not daring to do what supreme folly - the essence of life - calls me to do." I have followed folly much of my life. It has led me to here, this morning, slipping out of the apartment while everyone sleeps. |

||

(Posting Date 1 September 2006)

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||