|

The Atmeidan, or Hippodrome -- in Constantinople  Several years ago while on a holiday in Santa Barbara, California, I visited the Lost Horizon Bookstore on Anacapa Street, one of my favorite haunts. My attention was focused on the shelves that held old books about Greek history, classical Greek literature, and Balkan history. When I took a heavy book from a shelf and placed it on a chest-high cabinet to scan through its pages, steel engraved book illustrations that were lying there caught my eye. The first of these was of the harbor of Smyrna as it appeared in the mid-nineteenth century. It was an image of sea-men and passengers in small, wind-driven boats that rode the crests of breaking waves toward the shore. Putting the book back on the shelf, I turned to stud y the prints, borrowing a magnifying glass from the proprietor of the store so that I could see the details of the engraver's art. Before I left, I purchased six wonderful scenes of the Balkans, Ionia, and Epirus, and became interested in eighteenth and nineteenth century travel books that describe what were then mysterious and romantic regions known to western-Europeans as "Turkey in Europe," and The print, entitled "The Atmeidan, or Hippodrome," 1 is taken from The Beauties of the Bosphorous, a book by Julia Pardoe. Miss Pardoe (1806-1862) deserves a few words. She was born in Beverly, Yorkshire, Great Britain. Early in her literary career, she traveled to Constantinople with her father, a career military officer. While there, she wrote The City of the Sultan and Domestic Matters of the Turks, published in 1838. Her popularity as an author and her knowledge of Turkey led to publication of The Beauties of the Bosphorus, which was issued in three or more editions, the last in about 1855, just after the end of the Crimean War -- between Russia on one side, and Turkey, France, and Great Britain on the other. The artist, William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854), was born in Kentish Town. He was one of the pre-eminent travel illustrators of his day, noted for "faithful representations of scenes as he saw them." 2 The engraver, C. K. Richardson, can not be readily identified. He was one of the countless artists employed by London engravers. Miss Pardoe's and Great Britain's political and religious sympathies (anti-eastern European and pro-Ottoman), are made clear throughout the book, and are succinctly expressed in a florid style, in the final sentences of her introduction. [In the text that follows, the "Autocrat" is the Tsar of Russia, and the "lawful lords of the soil" are the Ottomans.]

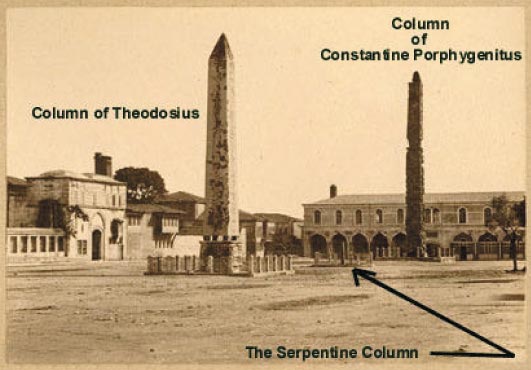

Before the time of Constantine the Great, at the turn of the third century C. E., the legions of Roman Emperor, Septimus Severus, conquered and destroyed the ancient city of Byzantion. In 203 C. E., after he rebuilt the city and expanded its walls, the Emperor constructed the Hippodrome, a sports arena that featured chariot races and other entertainments. One hundred years later, in about 324 C. E., Constantine decided to move the seat of the government from Rome to Byzantio n, which he called The New Rome and renamed Constantinople after himself. Located on the water route between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, and at the intersection of Asia and Europe, Constantinople was at the center of the changing geopolitical, economic, and religious life of the empire. When Constantine reconstructed and enlarged the city, one of his major undertakings was the renovation of the Hippodrome. Rebuilt, it is estimated to have contained an arena as much as 525 yards long (five football fields!) and 129 yards wide, capable of holding one hundred tho usand spectators. To raise the image of his new capital in the eyes of the Roman world and the barbarian east, Constantine brought works of art from all points of the empire to adorn it. Among these was the tripod of Plataea, an ancient monument that celebrated the victory of the Hellenic, civilized west over -- what they considered to be -- the Oriental, uncivilized east. It served as a reminder to eastern powers that their great armies had been crushed by the west. Constantine ordered the monument to be moved from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, and set in one of the most visible places in Constantinople -- the middle of the spina of the Hippodrome, the central axis around which chariot races took place. Today, all that remains of this monument is the Serpentine Column. This photograph of the Hippodrome, taken in the mid to late nineteenth century, shows the location of the Serpentine Column in a setting that is very unlike Bartlett's drawing.

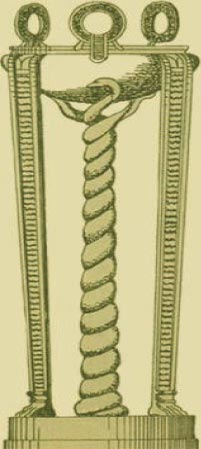

Thus, to honor their victory, the Greek cities constructed a golden tripod and mounted it so that its golden bowl rested atop the three heads of a bronze serpent. Its twisting body formed the Serpentine Column. Dedicated to the god, Apollo, the monument, one of the most important of ancient Greece, was placed next to the Altar of Apollo at Delphi. The names of the thirty-one allied cities that fought at the great battle were inscribed on the monument's base.

Another claims that when the Latin crusaders sacked Constantinople, they carried off the golden tripod, as they did countless pieces of the city's great works of art, and all of its riches. The serpent that supported the golden tripod may have had its three heads struck off by drunken members of the Polish embassy in 1700. Prior to that time the three heads appeared in miniature drawings. One of the heads can be seen in the city's Archeological Museum. What remains at the site of the Hippodrome is an unattractive, serpentine stump; an oddity whose history elevates it to the position of one of the western world's great artifacts.

The horses are believed to have been shipped to Rome by the Emperor Nero during his great tour of Greece in the 1 st century C. E. Three hundred years later, they were brought to Constantinople to adorn the Hippodrome, and they remained there for almost nine hundred years before becoming part of the plunder claimed by the Venetian Doge, Dandolo, who was one of the leaders of the Fourth Crusade. Napoleon took them from Venice with other loot after capturing the city, and placed them on the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel on the Tuileries in Paris. They were returned to Venice in 1815. (The horses atop the arch in Paris today are copies.) In 390 C. E., Theodosius the Great had the 800 ton, 200 foot high Obelisk cut into three pieces and brought to Constantinople. Only the top section survived, and it was placed in the spina on top of a marble pedestal. A photograph of one side of the pedestal is shown below. In it, Theodosius, who is ready to crown the victors, watches the races with his family. Visible in the distance to the left center of the illustration is St. Sophia (Agia Sophia) the great Orthodox Cathedral of Constantinople that was converted into a mosque after the city fell to the Ottoman's in 1453 C. E. Not visible in the illustration is the Column of Constantine Porphygenitus, 7 which was constructed in the tenth century C. E. It is out of view, to the right of the Serpentine Column. Originally covered with gilded bronze plaques that must have been a bright, shimmering wonder to the crowds in the stands of the Hippodrome, it is now an unattractive pillar of stone reaching one hundred feet into the sky. In 1204 C. E., during their rape of the city, the Latin crusaders helped themselves to the plaques — melting them down to mint coins that they carried away on their ships. Other illustrations in my collection have taken me on historical investigations similar to the one written about above. "The Straits of the Bosphorus" and "The Dardanelles, " both by Bartlett, led me to an exploration of the water route between the Aegean and Black Seas, with stops at cities that were ancient Greek colonies, and sites of historic battles from the time of Troy and the Greco-Persian Wars to the tragedy of Gallipoli. "A Pass in the Balkan Mountains," by Thomas Allom (1804-1872), and "A Street in the Suburbs of Adrianople," by W. L. Leitch, opened the door to the trade routes of the Balkans — following rivers and mountain passes through beautiful and 7 dangerous country. "Ioannina the Capital of Albania," by T. Allom, alerted me to the history of Ioannina prior to its annexation by Greece at the end of the Balkan Wars. I am grateful for the afternoon I spent at The Lost Horizon Bookstore, and the moment that my eyes fell on "Smyrna from the Harbor," by T. Allom, an illustration published in a book written by Reverend R. Walsh. 8 This engraving, I later learned, was executed by one of Great Britain's extraordinary engravers, J. T. Bentley, and was one of his "...finest plates..." 9 1 Also "At Meydani," translated from the Turkish as "horse square," the place of exercise for the 4 Herodotus, Robin Waterfield, and Carolyn Dewald, The Histories (Oxford [England] ; New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 574, Book Nine, Line 81. The "altar" is the monumental alter at the entrance to the Temple dedicated to Apollo by the Chians in the fifth century, B. C. E. 6 Emperor Theodosius the Great reigned from 379-395 C. E. He is celebrated for his work in law-giving and as an early defender of Christianity, who forbad pagan worship, and closed pagan temples. Back to Classics

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. |