|

||

|

Pergamum: Four Nations' Memories Athens News |

||

|

The dwelling place of Turks, Greeks, Armenians and Jews in Ottoman times, this important Hellenistic city - also known as the birthplace of papyrus' alternative - is graced with splendid public buildings. By Alex Penman

|

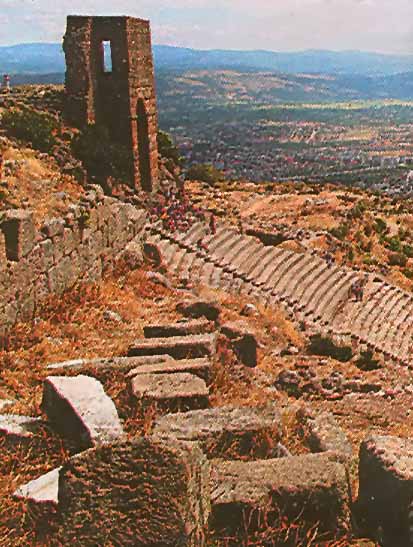

The ancient city of Pergamum (now Bergama) seen from the Acropolis with the theatre in the foreground |

|

After much haggling, we rented a taxi forthe day. The "old road" joining Ayvalik to Pergamum is an hour's journey through dense pine forests. As we ascended the hills, the temperature started to fall. The road passes a number of villages, whose inhabitants, our driver Ali informed us, are dedicated to the cultivation of pine nuts and wine production. Most belong to the Alevite sect - so did he. Noting our fascination at the environs, Ali proposed to stop for a glass of wine. The pine forests and abundant streams keep temperatures cool even in midsummer. What struck us immediately in the Alevite villages was the absence of a mosque: Alevites conduct religious services in shrines called cem-evi, where the men and women pray and dance together. Another striking sight was that of men drinking beer, not tea or coffee, in the cafe by the main square. No woman was covered. Pergamum's majestic Acropolis is visible miles away, dominating the town, whose old centre is surrounded by the amorphous mass of identical concrete blocks. Pergamum was once one of the most important Hellenistic cities, ruled by a series of tyrants who adorned it with splendid public buildings. Its fame was founded on its library. Continuing to flourish under the Romans, it was pillaged by the Goths and gradually declined. Pergamum was the culmination of Greek city planning, its layout making maximum use of its dramatic natural setting with the explicit aim to impress. As much as the Acropolis is impressive from below, it offers breathtaking panoramas, as impressive as its ruins. The ancient buildings were situated so as to exploit these natural surroundings to the full. Large parts of the Acropolis' most spectacular temple - the huge Altar of Zeus - were removed by the German engineer, Carl Humann, to Berlin in 1871 and are now on display in a purpose-built museum. Turkish authorities have been campaigning for their return. The altar was built by Eumenes II to commemorate the victory of his father Attalus over the Gauls. A frieze of statue reliefs depicting the battle between the Titans and the Gods, symbolising the triumph of order over chaos, surrounds its facade. The altar was described in amazement by writers of the Roman era. It is a pity one cannot admire it in its natural setting. Another victim of German rapacity was the 3rd century BC Temple of Athena, whose impressive two-storey main entrance was reconstructed in the Pergamum Museum. The northern aisle of the temple housed the renowned Pergamum Library, founded by the tyrant Attalus II. The library came to house 200,000 books. The Ptolemean Dynasty in Egypt was alanned, perceiving this spectacular growth as a threat to its own library in Alexandria. They responded by prohibiting the export of papyrus, of which Egypt was the sole producer, to Pergamum. Given that all books at the time were written on sheets made of papyrus, they believed this would offset the library's expansion. On the contrary, the prohibition led to an unexpected invention. Tyrant Eumenes promised a reward to anyone coming up with an alternative to papyrus. A technique developed for processing animal skin and using it as writing material. The product was called pergamene - after the city where it was invented - and is also known as parchment. Since the material was less elastic than papyrus and couldn't be similarly folded, it was cut into pieces, piled on each other and bound together - the modern, paged book. The library continued to grow despite sackings and other misfortunes and remained operative until the 4th century AD. The only temple to have survived is that of Trajan, dedicated to that Roman emperor. Huge Corinthian columns and part of its pediment survive, all in white marble shining under the sun. It was customary in Roman times to deify and adore the emperors, and in this shrine both Trajan and Adrian were adored We sat on the temple's steps to eat pitta bread with the parmesan Christiane had just brought over from Italy. A regular ritual of her visits to ancient temples, she claims it is her way of making an offering to the gods. Pergamum's other major archaeological site is the Asklepeion. Asklepeia dedicated to Asklepeios, son of Apollo and God of healing, dotted the Graeco-Roman world. In these centres a form of ritualistic medicine was practised. Patients were required to undergo a stage of "catharsis" before entering, while pregnant women and people expected to die were banished. No birth or death should occur in an Asklepeion. Operating aside, methods of treatment included dieting, bathing and exercise, but also music therapy. From the 4th century BC onwards, Asklepeia were built near thermal baths, used to complement treatment. Out of them sprang antiquity's most renowned doctors: Hippocrates, the founder of medical science, served in the Asklepeion of Kos, whilst his successor Claudius Galenus, better known as Galen, was born in Pergamum in AD 131 and educated in the local Asklepeion. He later lived in Rome and was the physician of Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Galen is perhaps the most renowned child of Pergamum. He crystallised the work of the Greek medical schools which had preceded him and remained an authority for more than a thousand years, until the Renaissance. Galen made full use of Pergamum's intellectual ambience, recei1ing an eclectic training, not only in medicine, but also in philosophy, letters and the arts. He regarded philosophy all essential part of training as a doctor, while advocating that a profit motive is incompatible with devotion to medicine: a doctor must learn to despise money. |

||

A medley of architectural forms at the old Greek quarters |

In the Asklepeion are the ruins of impressive colonnaded streets, once lined with arcades, a number of temples (the one of Asklepeios being the most important), a theatre and baths. The temple of Asklepeios was circular with a domed roof and was modelled on Rome's Pantheon; some of the other temples here were also circular, a type (rotunda) which developed in the Roman era. |

|

|

Little remains of the town, but one relic is conspicuous and preserved well enough to make up for the absence of others. The massive redbrick construction dominating the plain is the temple dedicated to the Egyptian Goddess Serapis, now known as Kizil Avlu (Red Court). The temple's bizarre silhouette makes an impressive ruin. Yet one is tempted to wonder whether its'enormous brick mass wouldn't have appeared monstrous, even threatening, dwarfing the modest-sized dwellings typical of Hellenistic cities. There is nothing alarming in the fact that an Egyptian deity was worshipped in the midst of a Greco-Roman city in Asia Minor. The Hellenistic, and later the Roman world, were quite cosmopolitan, with large expatriate colonies dwelling in major cities. A syncretic spirit presided in antiquity; deities and religious customs were exported and adopted with the same ease as styles of clothing and coiffure in the fin de siecle European salons. This liberty was erased with the advent of Christianity, whose rigidity did away with many more beautiful things of antiquity. The temple, built in the second century AD, was converted into a basilica during the early Byzantine years when Pergamum was one of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor that St John addressed in the Apocalypse. If he mentions Pergamum as ''home of the throne of the devil", he probably does so because of the resistance of the pagan religion, fighting for survival at the time. On the courtyard before the temple are scattered memories of a more recent past: a number of tombstones in Hebrew, most of them very plain, others with a section of Ottoman calligraphy over the Hebrew script lie amidst capital stones, fragments of column shafts and Greek inscriptions. Intrigued, we asked the guard about local Jews. A gentle man, he became visibly excited at my being Greek and amazed at the fact that a German and a Greek were fluent in Turkish. Halil explained how Ottoman Bergama was a city offour people: Turks, Greeks (whose houses stretched between the temple and the foot of the Acropolis), Armenians and Jews, with a strip of land each in the opposite side of the town. The river of Pergamum, now mostly dried, flowed through the temple precincts and divided the Greek quarter from the Armenian and Jewish one. "With the republic's proclamation we lost our minorities. I often sit and reflect on how richer -culturally and materially - we would be if they were still around, " Halil suddenly said. Nostalgia for the cosmopolitan past is commonplace in the liberal elites. Halil directed us to the non-Muslim neighbourhoods. The old Greek quarters are a medley of the various architectural forms that Asia Minor Greeks cultivated in the second half of the 19th century. Its houses are well preserved and its streets, quiet and deserted, are a pleasant stroll. Most of the houses are done in a rustic Ottoman style, simple cubic forms with the upper floors projecting. The rest bear marked influences of neoclassicism, the official line of the then recently established Kingdom of Greece: stone friezes under their tiled roofs, stone or brick door and window frames, wrought iron doors. Here and there, the dates of construction survive over the main doors, as sometimes do Greek names of months and the original owners' names. |

||

|

No church survives, but the beautiful building of a Greek school does. In an ornate neoclassic style, the building has a frieze with triglyphs and a beautifully carved pediment over its main door, depicting a book inside a laurel wreath - the book symbolising both knowledge and the town's history, where the parchment plays a central role. The ruined synagogue marks the once Jewish quarter, where no Jews are left. Hidden behind the garage, it is a marvel. An impressive canopy resting on Corinthian columns precedes the main door. Inside, the wooden ceiling is delicately carved and the bema, supported by Corinthian columns and done in the Ottoman baroque style, is also carved and painted. By all indications the building's collapse is imminent. An 18km ride along smooth hills and pine groves leads to the ruins of Allianoi, one of the ancient world's few surviving thermal complexes. Its springs are still usable. Allianoi is mentioned in leroi Logoi of second-century writer Aelios Aristeides, who was treated there. The settlement started as an Asklepeion, then developed into a spa centre under the Romans. What distinguishes Allianoi from other spas of antiquity is its uninterrupted use until modem times (1998). |

The massive redbrick temple Kizil Avlu is dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Serapis |

|

|

A group of archaeologists, most of them student volunteers, reside on the site and are racing against time. Professor Ahmet Yaras, presiding over excavations, stresses that unless Turkish courts interfere, Allianoi will be destroyed. "The water will flood the place with such speed that the remains will be shattered." |

||

The mosaic at Allianoi, one of the ancient world's few surviving thermal complexes |

|

|

|

Allianoi has divided local society. Farmers generally campaign for the dam, seen as essential for the development of local economy. Yet the town's mayor, the press and civil society are campaigning for the site's salvation, deploring economic progress at the expense of history and culture. A Committee for the Salvation of Allianoi was set up in Izmir; Europa Nostra and other bodies have voiced their support.

There is much to see in this ancient city, where memories of millennia lie on top of each other. Christiane and I decided to prolong our tour. Setting an appointment with Ali for the next day, we rushed to book a hotel room. And then set on to wonder, in peace, along the cubic forms of the Ottoman quarters..

From Istanbul or Izmir by bus, from Ayvalik by minibus or taxi. Ayvalik is reached by bus from Izmir or Istanbul. Olympic and T'urkish Airways have frequent connections from Athens to Istanbul and to Izmir via Istanbul

The best option is to lodge at Ayvalik, the atmospheric coastal town. Try the Zeytin Pansiyon, a tastefully restored house with garden (www.zeytinpansiyon.com); Bonjour Pansiyon, in a gorgeous house, with friendly staff. (Mara'Ial Hakmak Cad, Be'Iinci He'Ime Sok 6,0090 266 313 8085) and Taksiarhis, opposite the namesake church (0090 266 312 1494). In Bergama, try the Athena (0090 232 633 3420) and Pergamon (0090 232 633 43 43) pansions, both in old restored houses

In Ayvalik, try the taverns around the market of the island of Cunda (Moschonissi). In Bergama, head to Saglam 3 (Hukumet Cad 89), for stewed meats and kebabs or to Pala (Mescit Karacac) for fish |

||

HCS readers can view other excellent articles by the Athens News writers and staff in many sections of our extensive, permanent archives, especially our News & Issues, Travel in Greece, Business, and Food, Recipes & Garden sections at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||