|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

By Jennifer Gay Athens New |

||

| Driving through Attica on a hot day, it is evident which members of the plant kingdom are the survivors of a Greek summer. In July and August, with steady temperatures in the mid-30s Celsius, only, those adapted to harsh conditions provide colour and form to the landscape. The hillsides and mountains are cloaked in a dense, ever-green scrub (maquis) around two to five metres in height, often in areas where the true forest has been destroyed. Low prickly cushion plants, aromatics, bulbs and annuals make up the more spacious phrygana community of vegetation, where extensive grazing has occurred in maquis. Many of these species have developed methods to steel themselves against the elements and, though often regarded as merely a backdrop in the landscape, they can provide important structure in our gardens. I like using natives alongside other drought-resistant plants. Not only are many fine choices in their own right, but they also have lower water needs. Once established, these tough species last really well throughout the dry months with little deterioration in appearance. They also add year-round interest to planting arrangements, no matter how little attention they get. During a long hot summer, most plants suffer a certain amount of stress, Lack of water is the single biggest challenge they face: if they are to survive, they must adapt to searing temperatures, drying winds, bright light and solar radiation, Such powerful climatic factors put stress on the water balance of the plant by increasing transpiration (water loss from the leaves), A plant must maintain its turgidity, retaining sufficient water in its cells - one way is to reduce the rate of transpiration, The summer heat and winds further exacerbate the problem, sucking moisture out of the earth, The shallow and stony soils of Greece, poor at retaining moisture, make it even more difficult for a plant to get adequate water. |

||

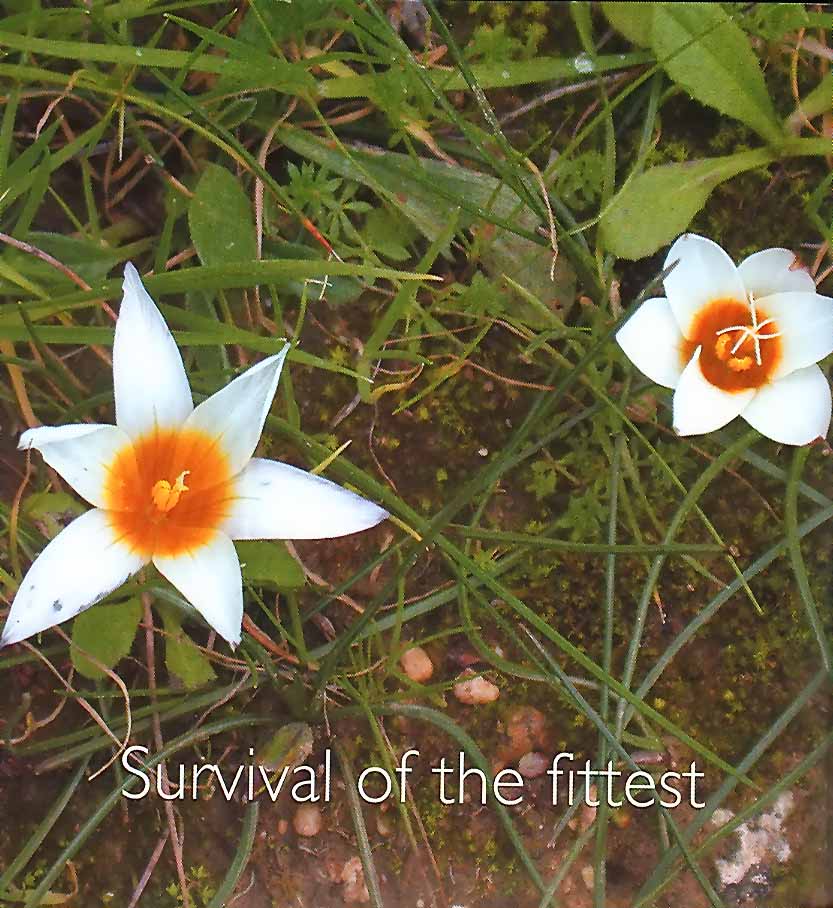

Perhaps the most obvious way to cope with such stress is to avoid it, as bulbs and annuals do. They complete their growth and flowering during the rainy months, between October and April. By the time the summer heat arrives, they are safely dormant. Bulbs (e.g. Daffodils, Lilies), corms (e.g. Crocus, Cyclamen) and tubers (e.g. Dahlias) spend the summer under-ground as storage organs, while annual plants survive as seeds. This is, of course, the reason why Greece has such a huge number of plants flowering in spring, all anxious to complete their life cycle before the heat hits home. Plants that remain above ground provide long-term interest for the gardener. Tree Spurge (Euphorbia dendroides) is a drought deciduous plant, which simply means that it loses all its leaves in summer (exactly as many broad leaf trees do in winter to avoid the cold). With the arrival of the autumn rains, the leaves reappear. |

Tree Spurge (Euphorbia dendroides) |

|

Other plants don't vanish, but reduce the area exposed to the elements: Spanish Broom (Spartium junceum) has tiny, tiny leaves and largely confines photosynthesising activities to its stems. The branch tips are spines, which also protect it from grazing animals. Plants of the maquis - such as Kenmes Oak (Quercus coccifera) , Lentisc or Mastic (Pistacia lentiscus), Myrtle (Myrtus communis) and Mediterranean Buckthorn (Rhamnus alatemus) - are also excellent summer survivors. They are sclerophyllous, that is, evergreen with tough, thick leaves, which are often hard and spiny to touch. Such leaves are very good at cutting down on water loss, because they have thick cuticles, as well as a light-reflecting, waxy coating. Additionally, they can close their stomata (the minute pores on the leaf or stem, which exchange gases and release water vapour) when under duress. These evergreen shrubs, so common throughout Greece, prove very useful in the garden. Many make good subjects for wind-breaks. Also they usually respond well to clipping and can be successfully used in more "controlled", formal parts of the garden. Some members of the pea family close their leaves to avoid sun exposure, which makes them good drought-resistant choices. The native Tree Medick (Medicago arborea) has this ability: reaching two to three metres, with golden-yellow flowers and intriguing coiled seedpods, it is a good plant for naturalising on a stony hillside. The Spurge Olive (Cneorum tricoccon), a native of the West Mediterranean, holds its leaves vertically to reduce the area exposed to the sun. Once established, it's very tough and copes without any additional irrigation. Other plants position their leaves to create shade internally, one leaf shadowing the other. Many deciduous trees use this method. Other species retain water vapour on their surfaces. They use tiny microscopic scales, felt-like or woolly to the touch and most effective in reflecting heat and light; these give plants a silvery or greyish bloom. Mullein (Verbascum) is a classic example, but there are many others using this technique - including Wormwood (Artemisia arborescens), Cineraria (Senecio cineraria), Jerusalem Sage (Phlomis fruticosa) and Lamb's Ears (Stachys byzantina) - all wonderful plants for providing foliage contrast in the garden. As well as changing leaf shape, form and position, some species have evolved their whole structure to reduce water loss. Greece is home to many 'cushion' plants, such as Greek Spiny Spurge (Euphorbia acanthothamnos) and Thorny Burnet (Sarcopoterium spinosum). These restrict their annual growth rate, saving energy to endure dry periods. Small, gradual growth results in a compact rounded appearance of a uniform shape and size, hence the 'cushion' nickname. However, don't be deceived, as these plants usually have an additional adaptation: prickles! This quickly disqualifies them as potential seating material, but more importantly, makes them unlikely fodder for passing goats. So they have survived countless years of over-grazing and are perfect for coping with the most exposed and sunburnt hillside. The secretion of aromatic oil is the drought-survival characteristic most evocative of Greek plants perhaps. This quality not only endows plants with lovely scents, but also reduces water loss by retaining vapour on leaf surfaces. The oils further protect the plant by making it unattractive to grazing beasts. Most Greek herbs have this ability and are too numerous to mention, but Lavender (Lavandula species), Oregano (Onganum species), Thyme (Thymus species), Sage (Salvia officinalis) and Curry Plant (Helichrysum italicum) stand out. The native plants of Greece are survivors. They exist here under taxing conditions because they have evolved to do so. Many adaptations - and resultant lower water needs - actually make the plants attractive and worthy of a position in any garden. A wealth of horticultural inspiration awaits discovery in the native flora. The biggest irony is, that more often than not, local plants cannot be found in the nurseries of Greece. We have to look further afield (from suppliers abroad) or propagate them ourselves. |

||

(Posting date 7 June 2006) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||